WEATHERING AND MARKINGS, PART-2

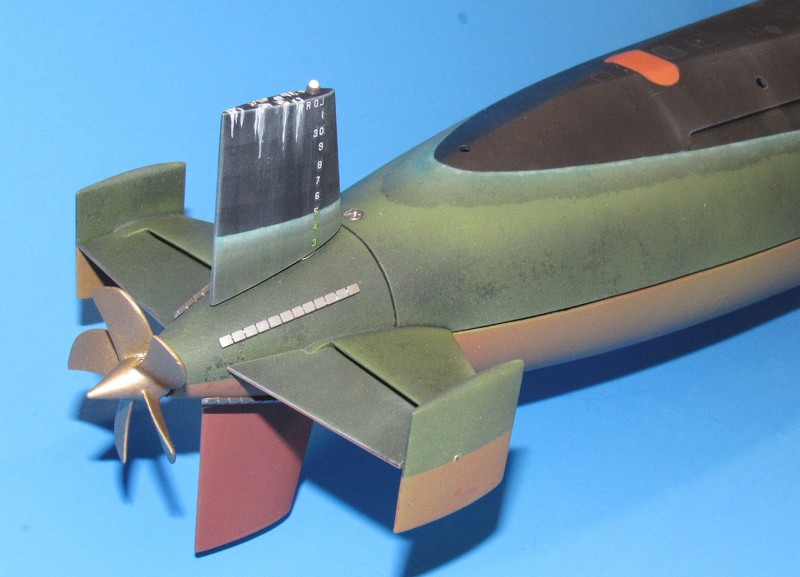

Oil Canning Relatively thin, non-pressure hull portions of the submarine are subject, over time, of the phenomena of 'oil-canning', not always the sole result of wave action, but most often given as the cause. What is evidenced is the dishing in of the plating over the supporting network of stringers, platforms, frames, ribs, and bulkheads. On modern submarines oil-canning is most evident on the control surfaces, stabilizers and sail. A most effective way of representing oil-canning is to shade in a pattern that conforms to the understructure -- the darker portions of 'shade' to be behind the imagined raised portions of plate held proud from the understructure. To do this you have to assume a point in the sky from witch sun-light is striking the surface. This is the sort of thing you want to practice extensively on a handy test-article.

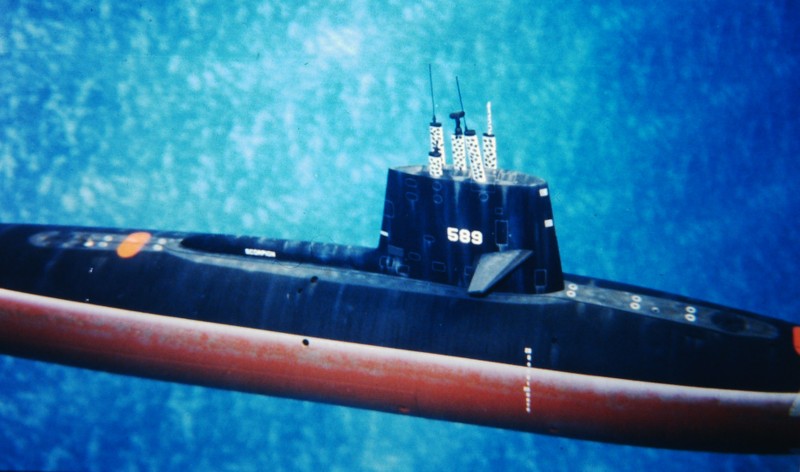

Information on plating understructure for modern submarines is hard to come by. One rather grisly source for working out such structures are the recently declassified detail survey photos of the sunken SCORPION. In that case the extreme deformation -- the result of sea pressure and the shock of the implosion event(s) revealed the locations and pattern of such dishing.

Studying sunken SCORPION photos I worked out where the frames, spars, ribs, frames, and stringers went for the rudders, horizontal stabilizers, stern planes, sail planes, and sail. It was all there.

The stuff of nightmares. Nobody drowned!

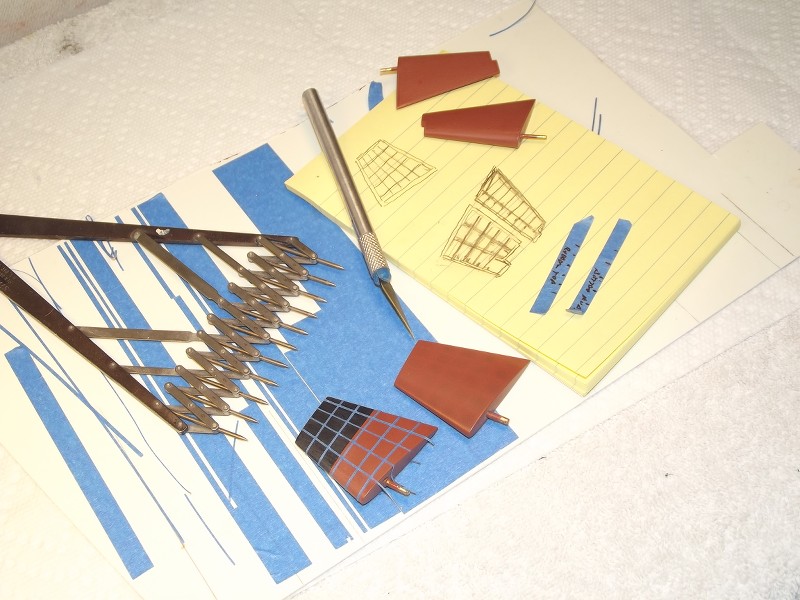

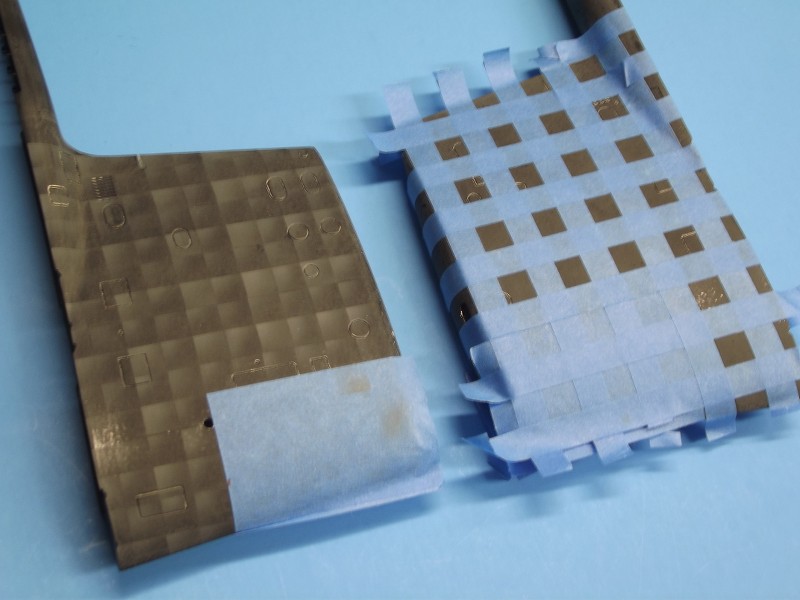

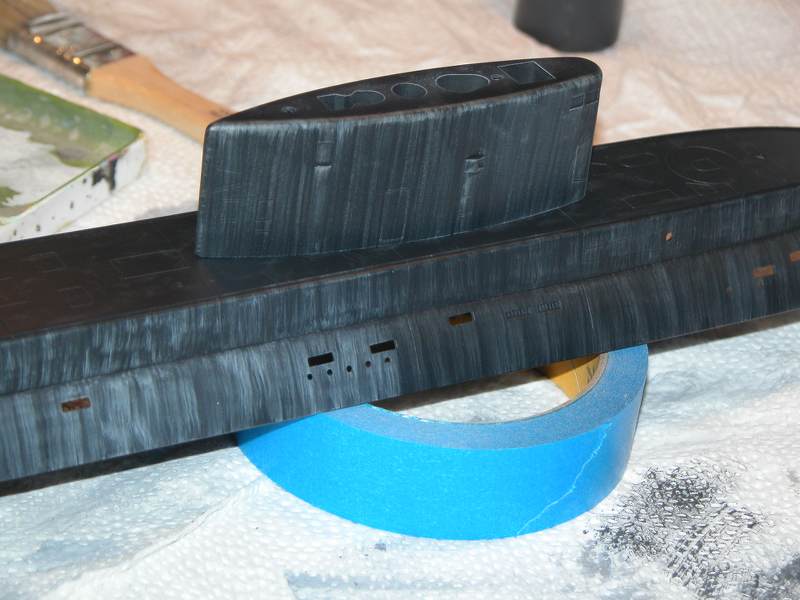

Masking is simply a checker-board array of strips of masking tape whose width is that of the spacing between stringers and frames. Once the squares are masked off a lighter shade of the black-gray or anti-foul red primary paint is mixed up, loaded into the air-brush, and applied to those areas of each square in line-of-sight with the imagined sun source.

Removing the masking inevitably reveals uneven applications of 'shading'. This is corrected by loading the gun with the primary color and shooting selected areas of the work till the oil-canning has been evened out and toned down to an acceptable level.

As doors, access hand-hole plates, and other points with removable plating will not conform to the run of frames and stringers, those are masked around and the base color applied. The same stencils I use for scribing serves here as quick and dirty painting masks to cover those access areas on the sides of the sail

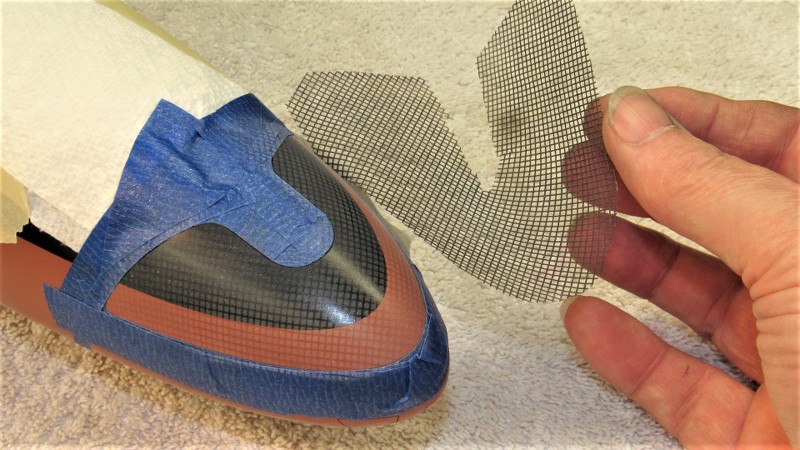

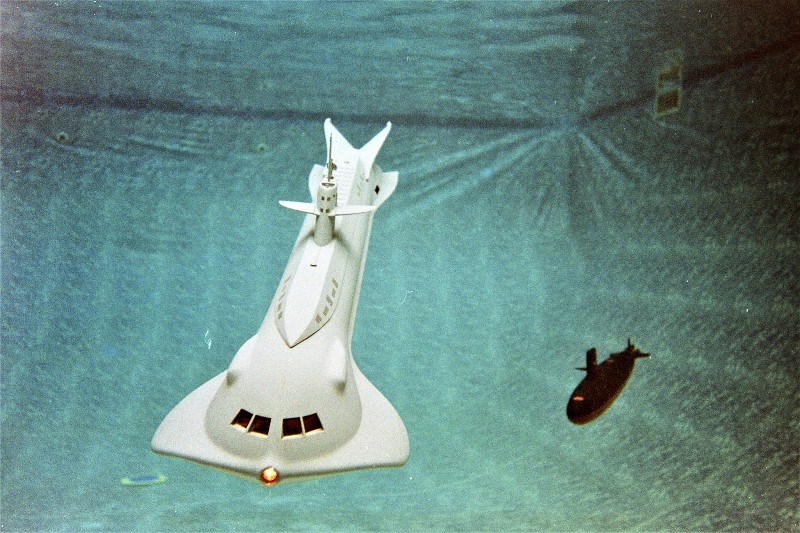

Like metal plate oil-canning, the phenomena of sonar window sagging over its geodetic underworks is a look you should exploit. This is best achieved by using plastic window screening as a mask.

Here you see it not only used to suggest GRP sagging into the voids between understructure bracing, but also used to suggest anechoic tiles on hull and sail.

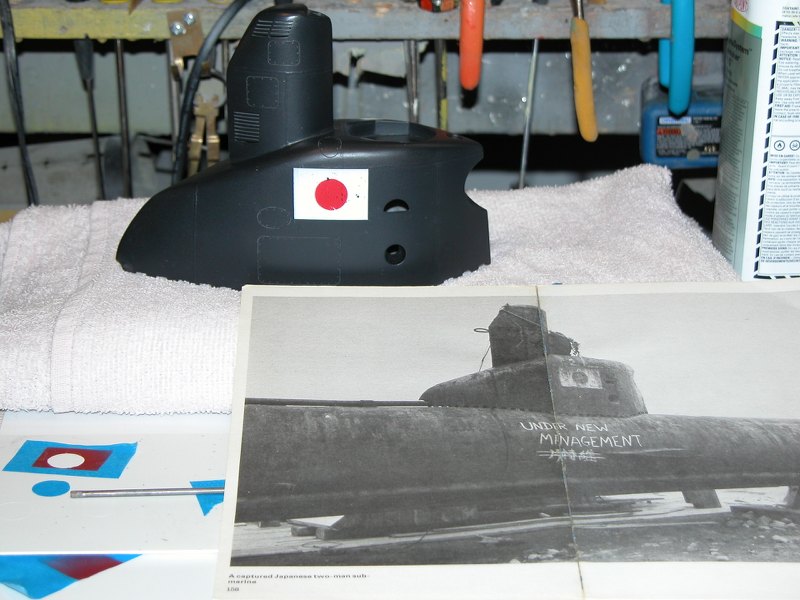

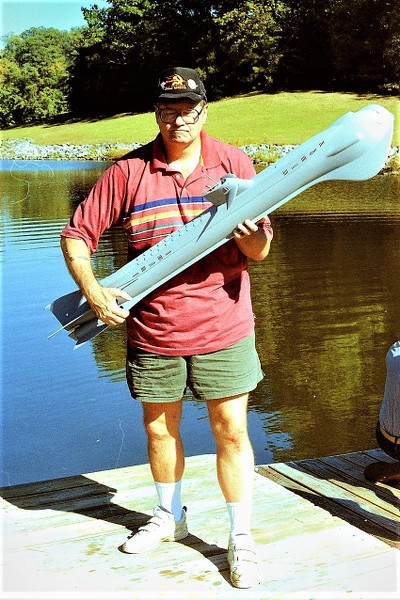

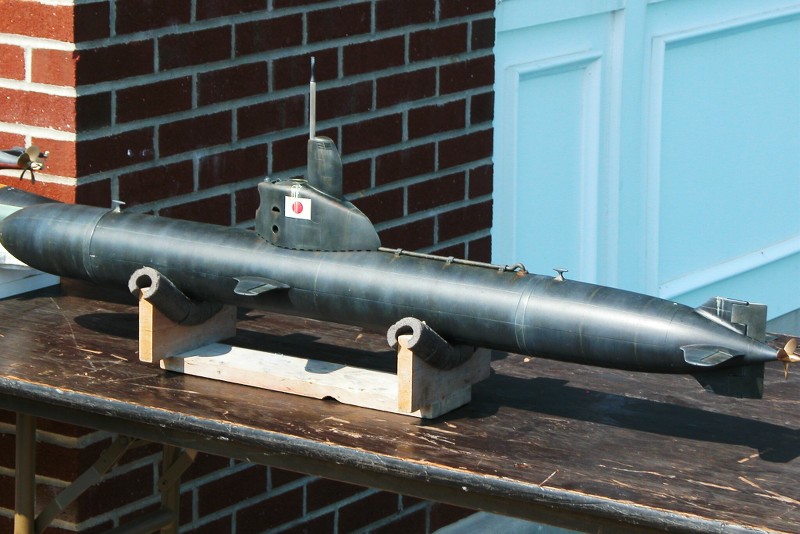

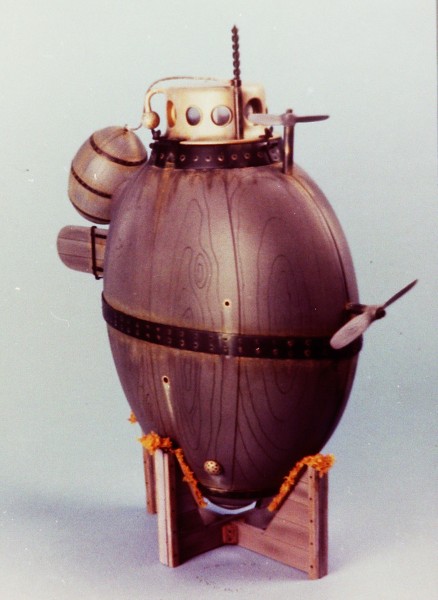

An old-school masking medium is rubber cement. You dab it onto the model surface, paint, then lift the mask off with sticky masking tape. A good example is the paint-failure effect seen on the Japanese flag that adorns both sides of this 1/16 KAIRYU midget submarine model.

Markings Hull numbers, draft numbers and bars, hull name, technical markings, high visibility items like marker buoys, and the like, though not 'weathering' go hand-in-hand with those operations as the two activities are right next to one another if your chronology of events is a rational one. And many of the marking techniques do involve one form of masking or another.

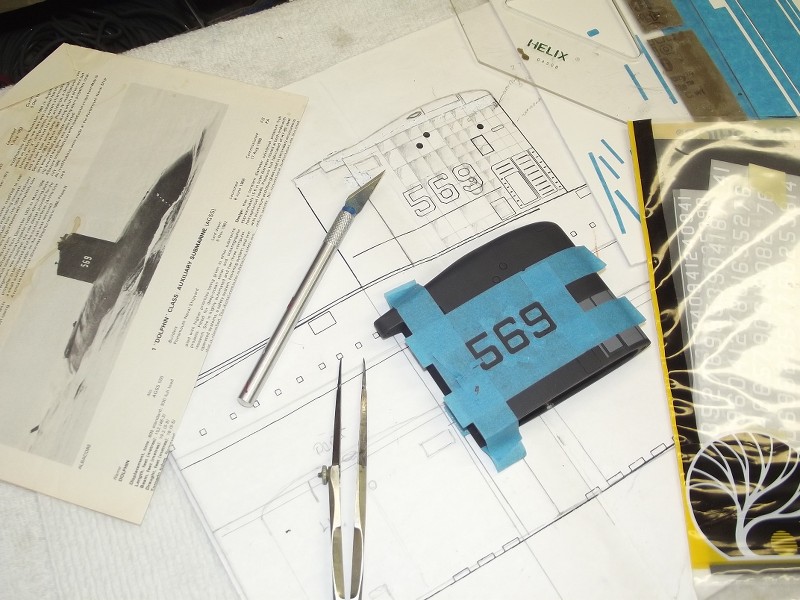

There is the old standard for markings: masking tape. Here you see it used to mask out Roman Gothic font hull numbers. You plot location and size, put down the tape, paint, remove masking and wa-la, the desired numbers in the color of choice.

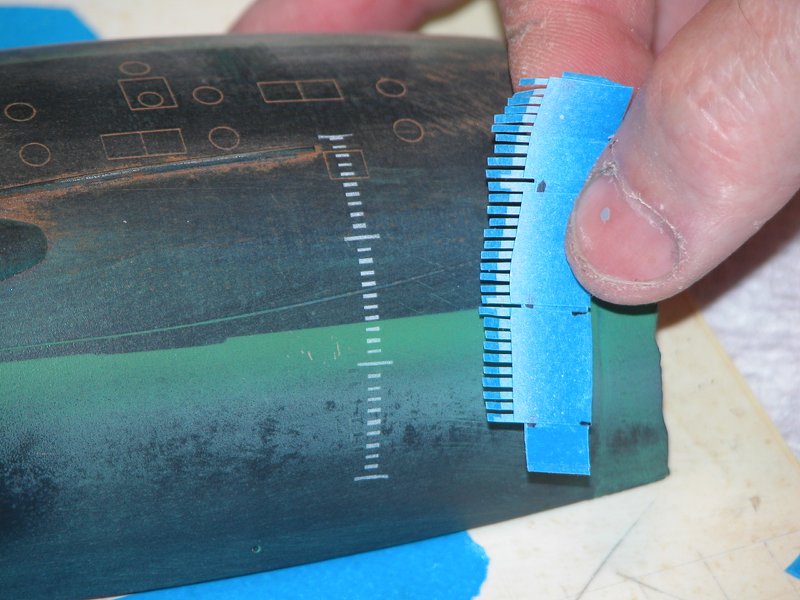

And going the masking tape route of producing the European style of horizontal bars that denote draft level of the in-port submarine.

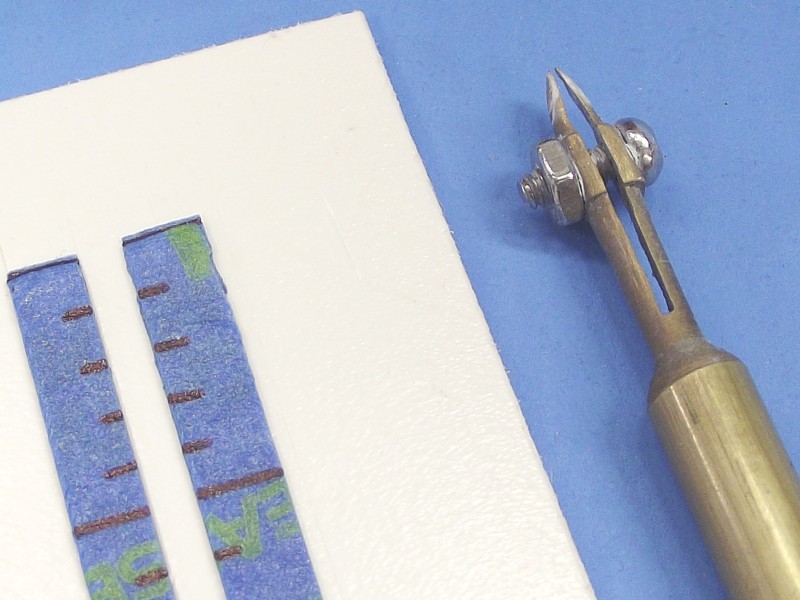

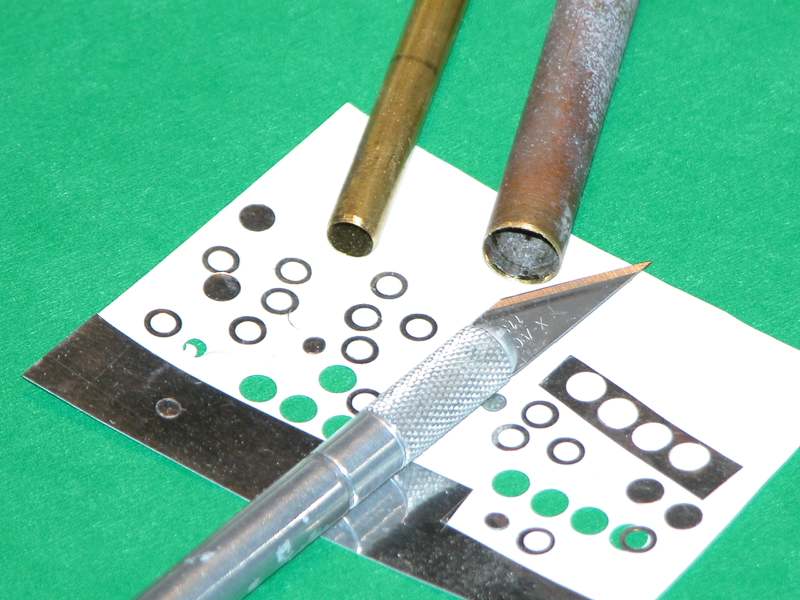

Cutting out circles onto masking tape is either done with brass tube punches, or a compass cutter.

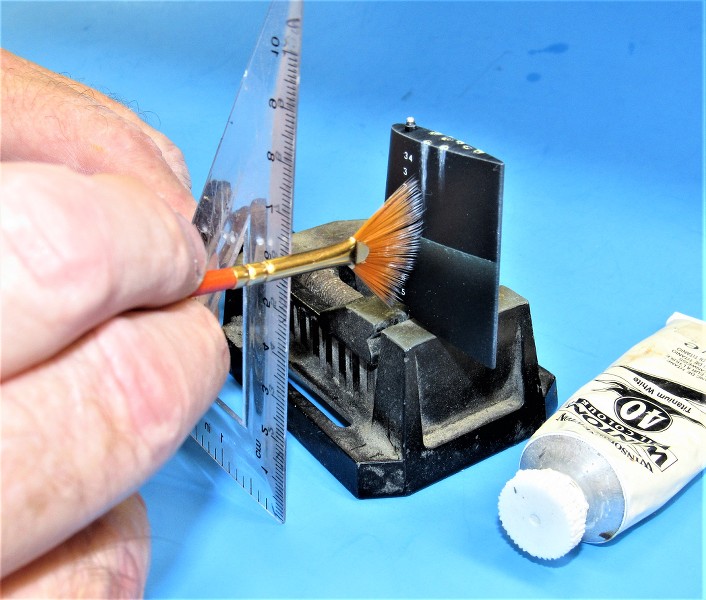

I've found a home-made 'drafting pen' very useful when I need to lay down narrow, uniform lines. Such as European draft markings, technical markings, and mild radius boot-topping. Here you see the use of the drafting pen as I put down horizontal lines denoting draft heights on the sides of this 1/96 KILO hull.

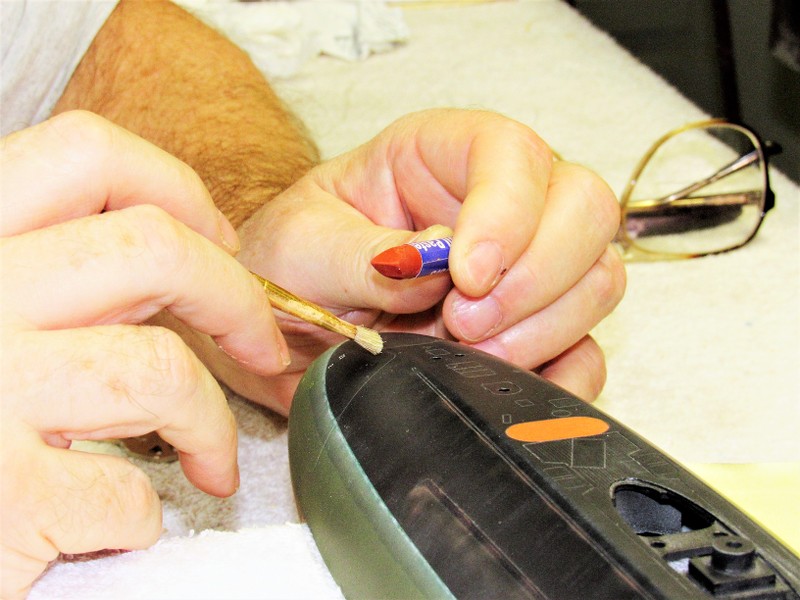

A concern with using dry-transfer and water-slide type decals is that they, because of their week adhesive bond to the models surface, is the need to defer their application until all the gross weathering has been applied. That's because some weathering techniques require use of high-stick masks and abrasives -- techniques that easily damage fragile markings. That results in the need to spot weather those markings to match the surrounding colors of the weathering. That's what I'm doing to the hull draft numbers (that job already done on the foreground upper rudder draft numbers. The job done with water thin acrylic paint applied in multiple coats, drying with a heat-gun between coats dill the desired opacity is achieved.

Dry transfers themselves, taking advantage of their weak bond to the models surface, are also employed as painting masks. Once the work is done, masking tape is used to lift off the dry-transfer revealing the underlying color in a perfect pattern of the dry-transfer that protected the underlying paint. A neat trick when you need numbers/letters in red but only have white dry-transfers.

Or, dry-transfers can be used as God intended: press-on type markings.

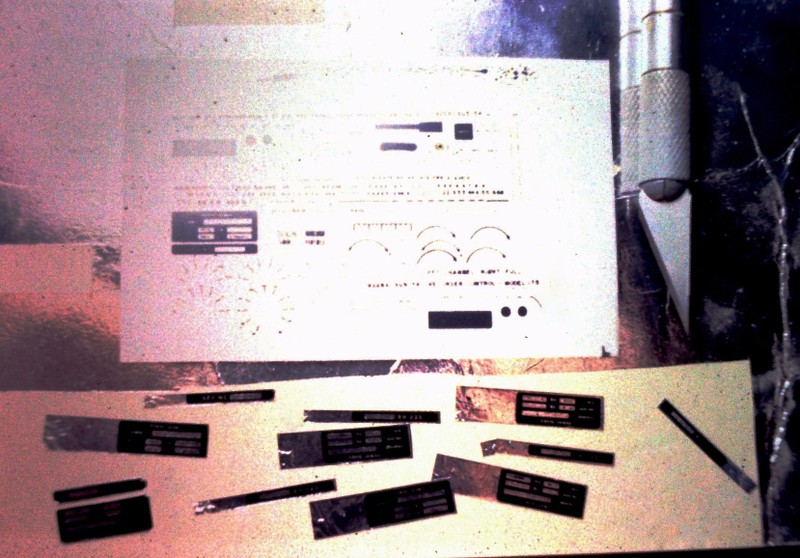

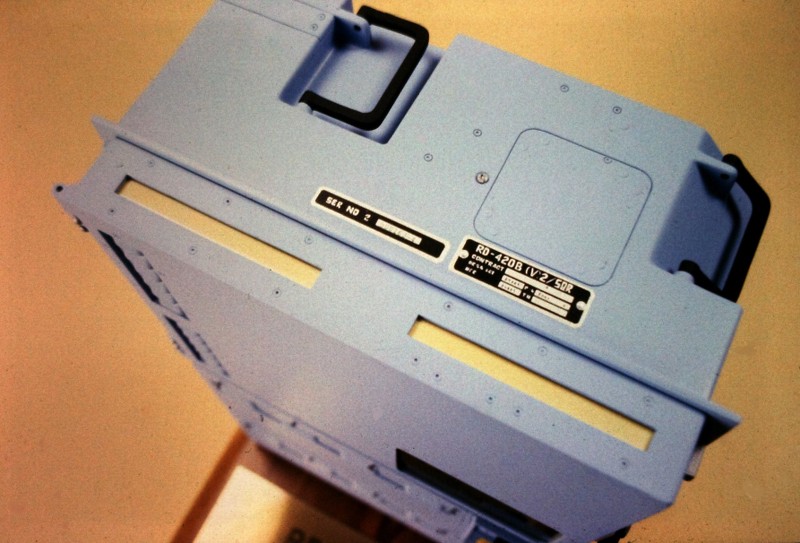

If you need 'information plaques' or 'machinery nomenclature plaques' you burnish down dry-transfers to self-adhesive aluminum foil and apply that to the displays surface, which is what you see done for this industrial promotional model.

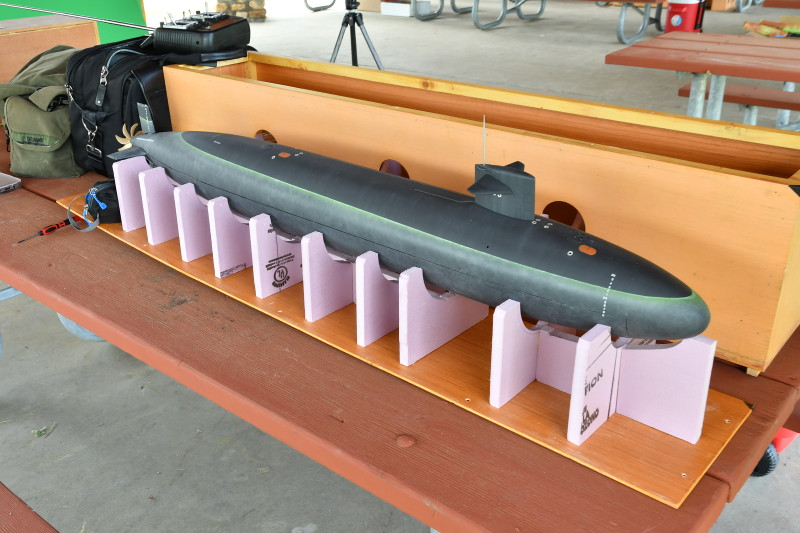

Streaking Before launching into this most useful, and difficult to master, weathering technique let me circle back a bit: I've mentioned the use of 'test-articles' before. These simply are training-aids you keep at hand; discarded hulls you may or may not complete in your lifetime. But hulls representative of the geometries of the type models you enjoy working on. These test articles are what you practice a painting, assembly, weathering, or marking technique on if you are unsure of yourself and don't wish to bugger up the project at hand.

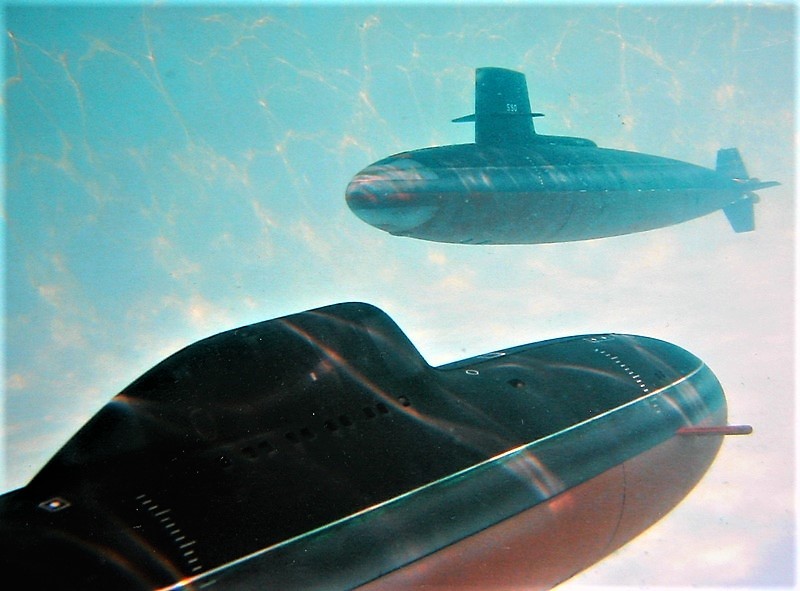

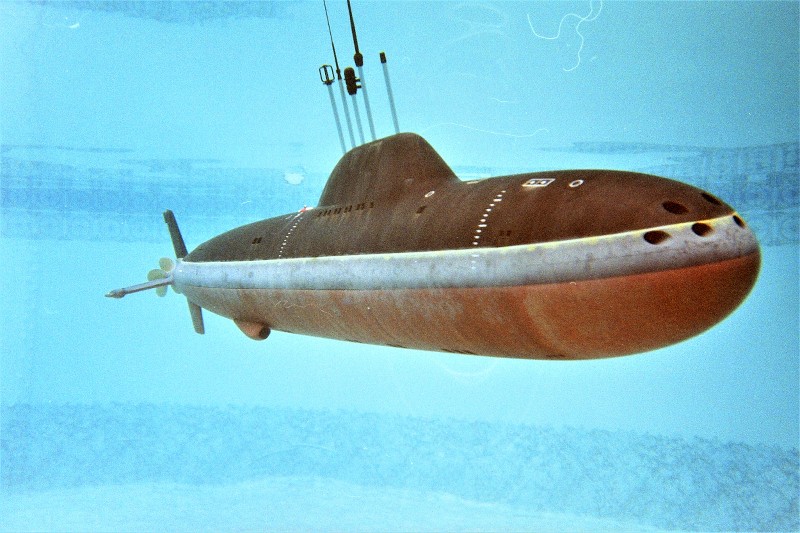

You practice and perfect your techniques on the test-article and only move on to the display piece when you're ready. Here are some examples of test-articles in my shop and some of the training I've done on them:

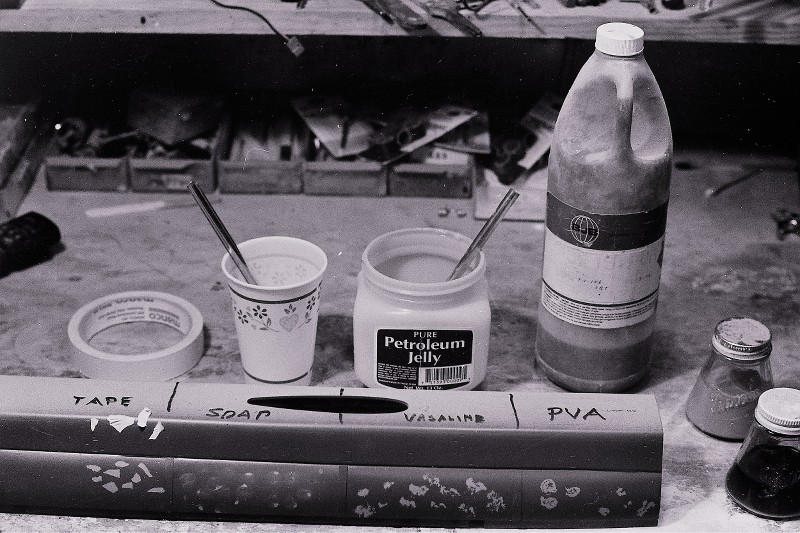

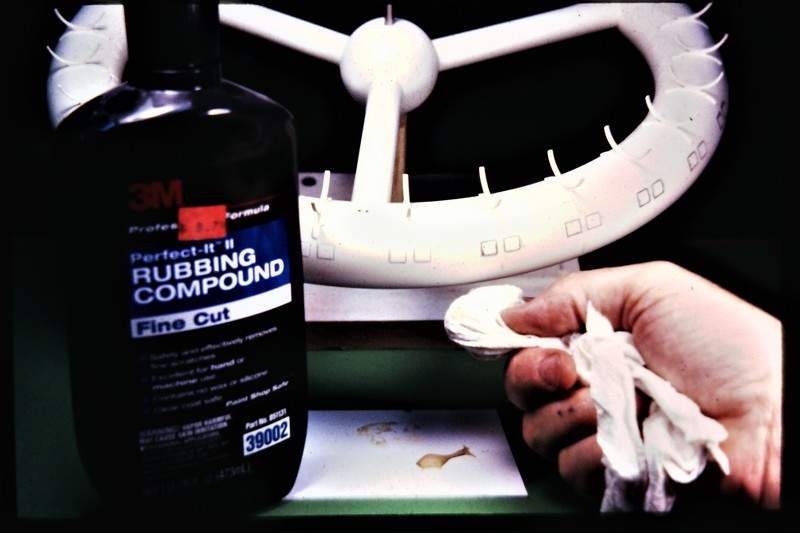

During my formative years I began to experiment with the more exotic masking materials and application techniques. This was one of my first test-articles, a never finished 1/96 USS NAUTILUS hull section. Note that I've segregated into sections where I could test specific masking mediums. Evaluation taught me that good old tooth-paste was the best for the work I did; PVA came in a very close second place.

That same test-article used to explore different tools and techniques for laying down water-soluble acrylic paint for WL scum and vertical streaking study. Awful looking work here -- that's why you commit your worst work to something people will ever see. Nuts!... I should have thought that through before posting that picture. Now I will have to kill you all! Sorry.

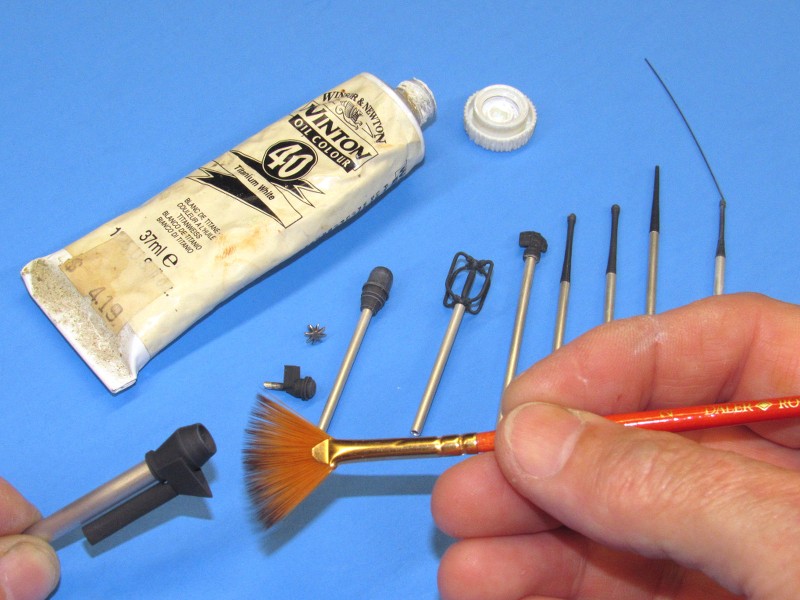

I temporarily pressed one of my 1/96 SKIPJACK hulls into service as a test-article. Here I'm playing with pre-shading techniques as well as working on my blending skills with oil paints using a variety of brushes, texture sticks and cotton balls. I also played around with Artist's pencils exploring their utility at representing scum lines and marking touch-up tasks.

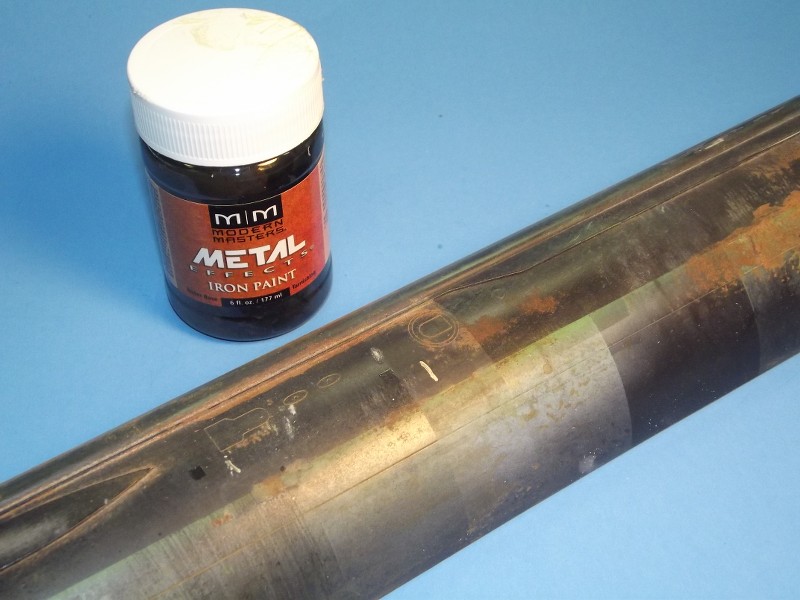

This long suffering 1/144 Trumpeter SEAWOLF kit hull has seen it all! At this point I was evaluating several brands of 'real rust' medium. With the right acid, and some skill swirling it around, an astoundingly real look of rust can be achieved. Because, duh, it's real rust!

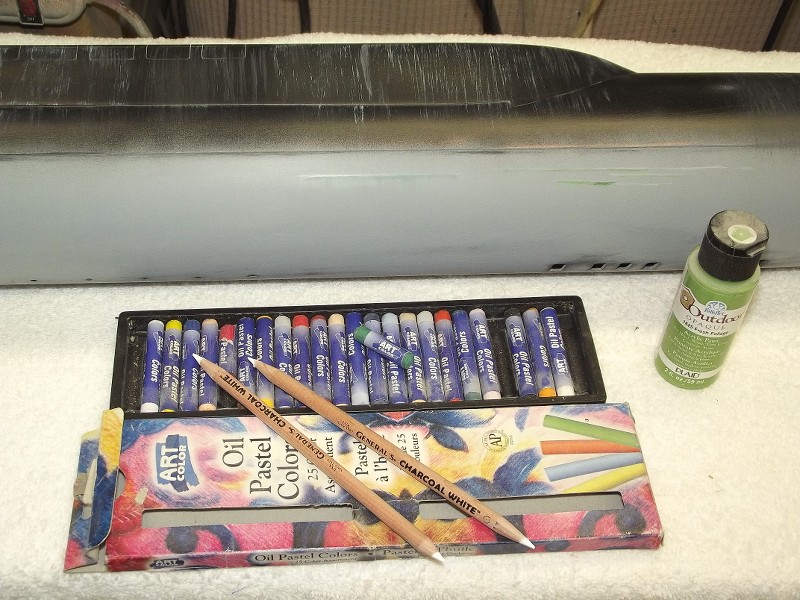

I'm using the SSBN test article to play with oil pastel crayon smears. You put a glob of this medium on the model then pull it into a streak or localized pile of gunk with stiff chisel brushes. I've found the crayons good for that off-color band(s) seen just below the WL. Dip your brush into linseed oil and the work goes a lot quicker.

And this look at the use of test-articles leads us right back into the technique of 'streaking'. Here I'm investigating the means -- through use of a right-triangle guide rail (a length of channel running the length and parallel to the hulls longitudinal axis) -- of achieving near perfect vertical sweeps of the lightly loaded brush as I lay down vertical paint streaks.

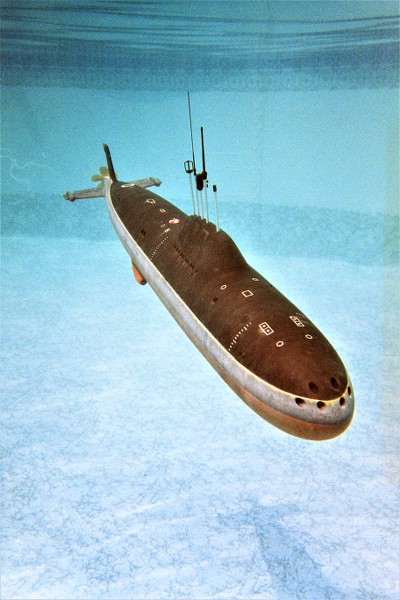

The streaking effect represents rain-water run-off along the sides of the hull and down the upper rudder and sail (and any other structures AWL unique to the subject). Streaking goes down in two stages: the light colored streaking followed by a misting of the base color to soften the effect as, like oil-canning, the application will always be a bit too stark than desired, so you tone it down with a well cut mixture of the base color.

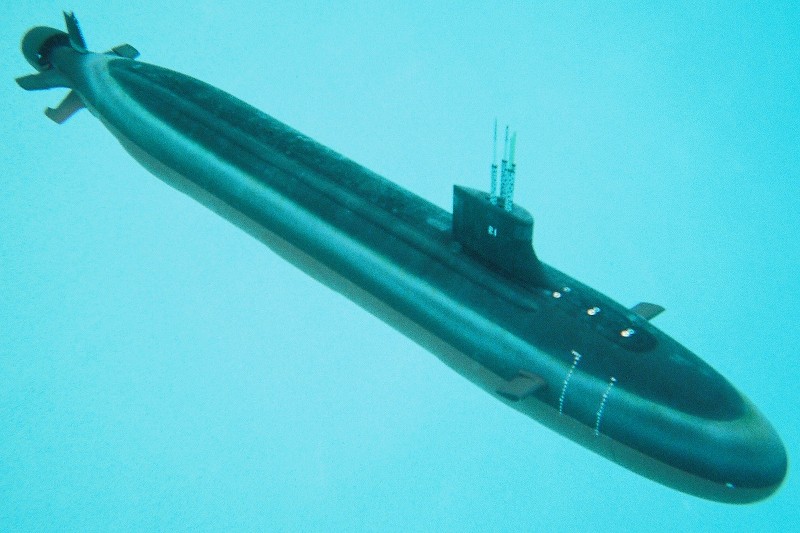

NEVER represent vertical streaking on the BWL portions of hull. Just don't happen! (Other than water run-off from discharges still active in dry-dock, but that's an exception to a boats natural in-water look). That's why the masking from WL down on this 1/60 ALBACORE hull I'm streaking with acrylic paint. I prefer the quick-dry, water-soluble paint for this work as the steaks will not blend with one another when dry; nor is this paint soluble once dry. For that reasons I don't use oil paint or other blindable mediums when doing this type work.

I've demonstrated here on this 1/144 Trumpeter KILO how to de-emphasis the streaking by misting on the appropriate amount of base color to knock down the contrast. The misting is done with vertical passes of the air-gun. NEVER horizontal sweeps!! To the left is virgin streaking; to the right I've misted on some base color to present a more credible look to the effect.

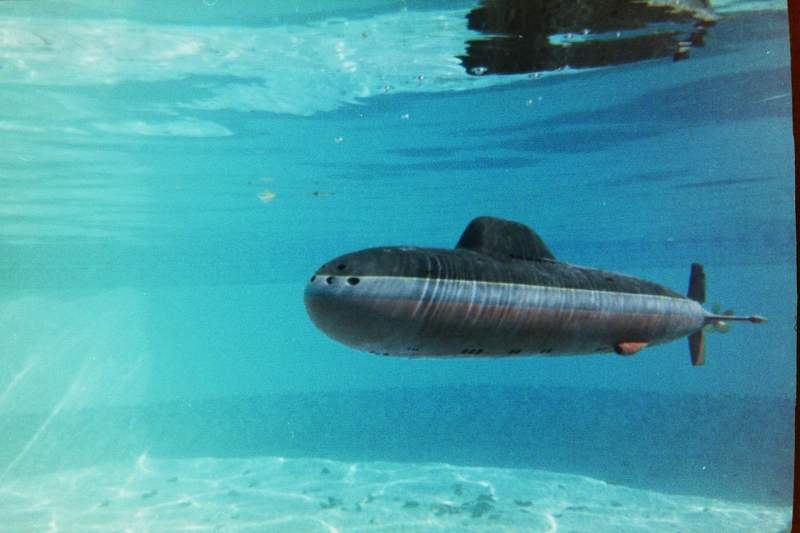

And the result. Not a pristine, toy looking model. But an honest to God, attractive display piece representing a REAL, operational, weather beaten submarine. That's what weathering is all about -- that final step taken to breath life into the work; a living, breathing thing subject to the effects of the environment it operates in.

Metallics Nothing looks like bright metal like bright metal. The best medium is self-adhesive aluminum foil. You can make your own from Reynolds Wrap and contact cement, or you can buy the commercial stuff at the local hobby shop (rotsa ruck!). Second best medium are the metallic particle bearing waxes like the old Rub n' Buff products.

Self-adhesive aluminum foil is usually used to represent the stainless steel flange rings around main ballast tank vents as well as the the cover plates of compartment salvage deck fittings. On the real boats these items are usually painted black, but I show them this way to increase visibility of the submerged model.

Here I'm using brass tube punches to cut the concentric circles that produce MBTV flanges.

Once the flanges are cut to shape they are lifted off the backing paper (wax or parchment paper) with a blade tip and transferred to the model.

Use of Rub n' Buff silver wax to render a 'clear deadlight' look to a 1/60 ALBACORE's bridge wind-breaker. Care is taken to mask around the work as once the wax gets away from you it can only be removed through abrasion or scraping.

The metallic wax, with care, can be worked onto the model surface with a stiff chisel-brush with surprising accuracy. And the more you brush and buff it out, the brighter becomes the metal flakes suspended in the wax binder.

Such as the pipe runs on this Disney NAUTILUS wheel-house interior.

Oil Pastel Crayon Solid sticks of oil paint, if you will. You position a hunk of this stuff where you want it then knead and pull the medium with stiff brushes to feather it out. Good for spot-rust effects, cathodic bleaching, verdigris and the like.

The bleached band at the top of the WL scum band -- representing dead flora at the water/air interface -- was too stark so I softened that band down with smears of green oil pastel crayon and then feathered it into the work with brushes and a cotton ball.

Carbon exhaust streaking from one of the main engine exhaust ports is done with crayon -- little wads of the stuff is placed under the exhaust port and streaked downwards with a stiff brush. I've just started the blending here, it will become more of a unified, coherent streak by time I'm done with this task.

Rusting on modern submarines is hardly apparent, so this is an effect you either don't do or do with a very light touch. I can assure you, if I don't see it on the prototype, I don't do it on the display! Less is more.

Chalk Pastel and raw chalks have their place. They go down and when ground to a powder can be manipulated into harsh streaking or soft, feathered runs. However, once overcoated with the clear-coat they will diminish greatly in density, so to be effective the chalk has to be laid on thick to compensate for this. An acquired art.

Chalk is also used, in lieu of dry-brushing, to pick out light gathering projections, such as these white-caps on this water scene.

Comment