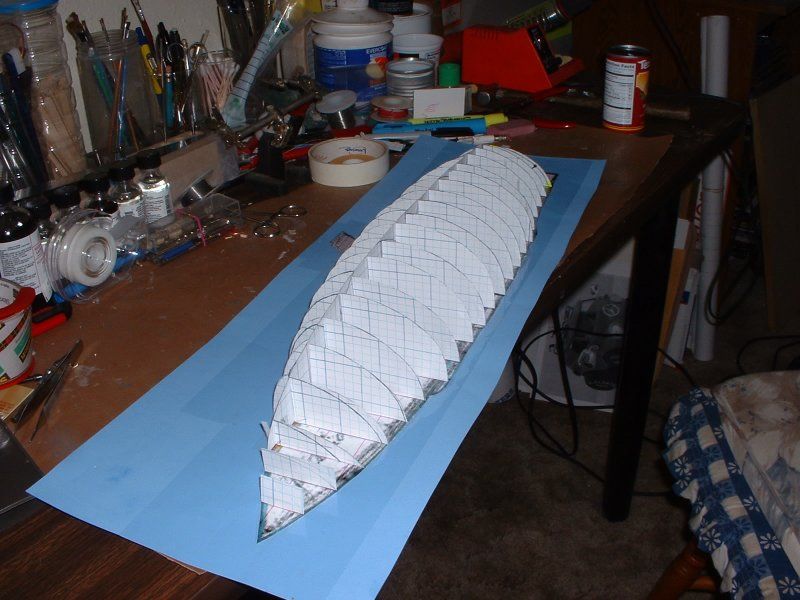

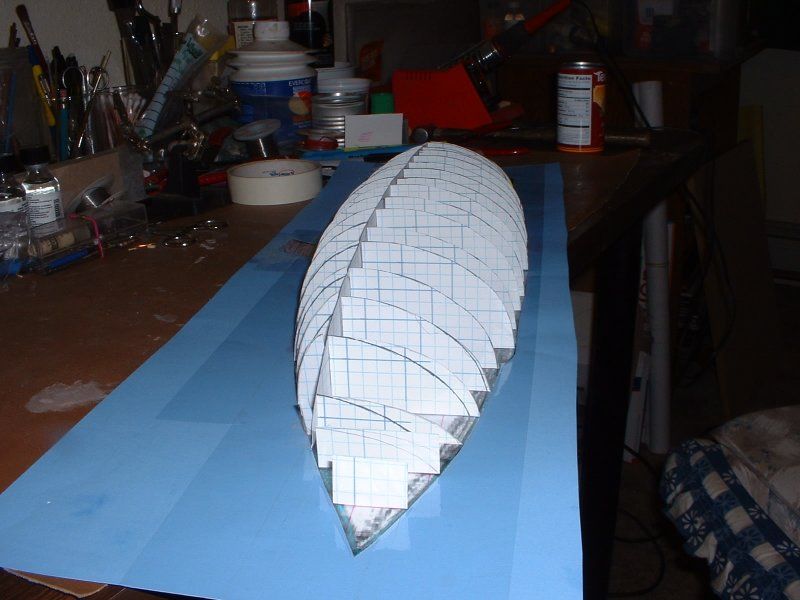

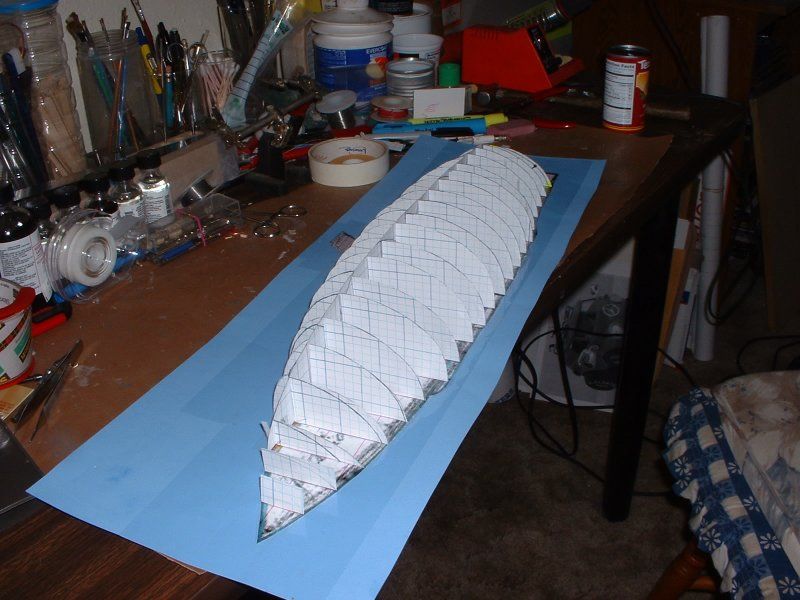

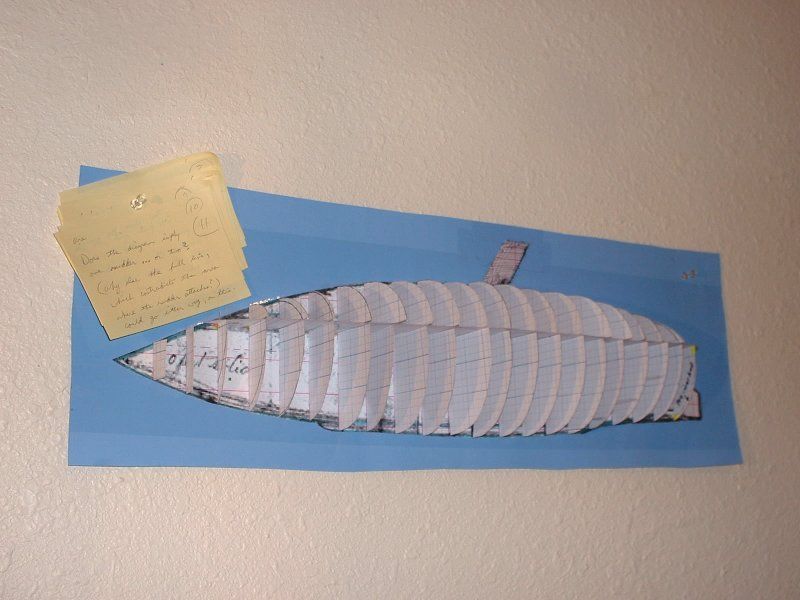

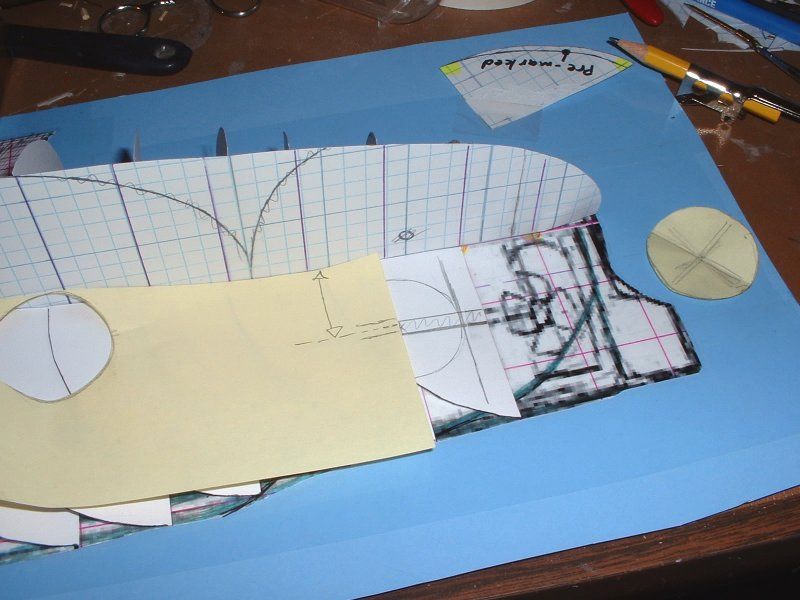

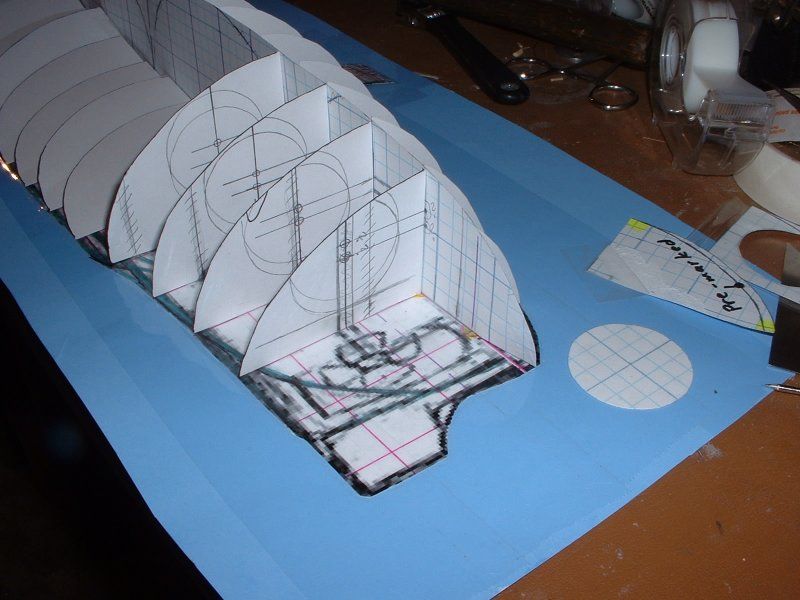

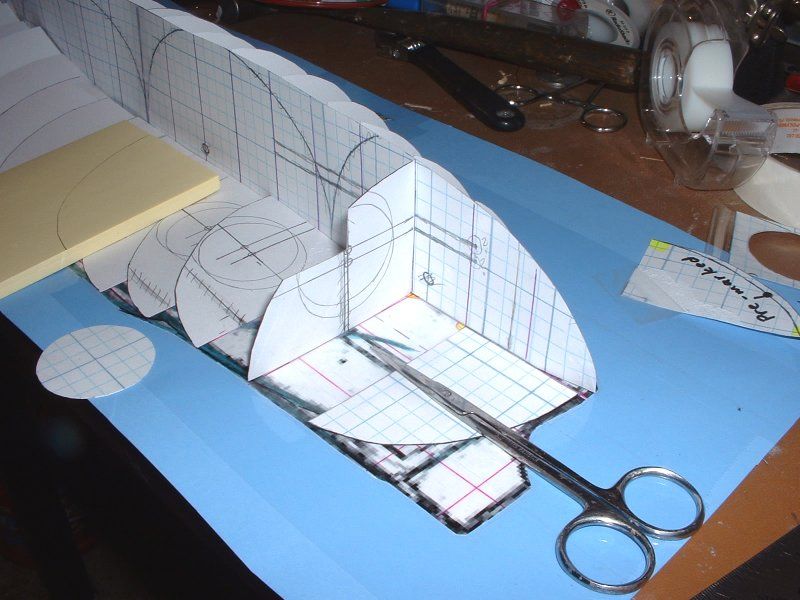

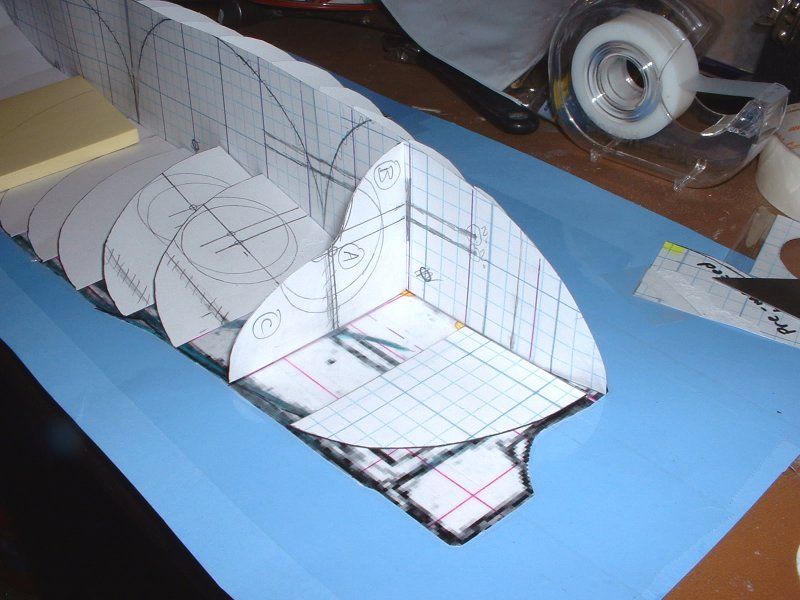

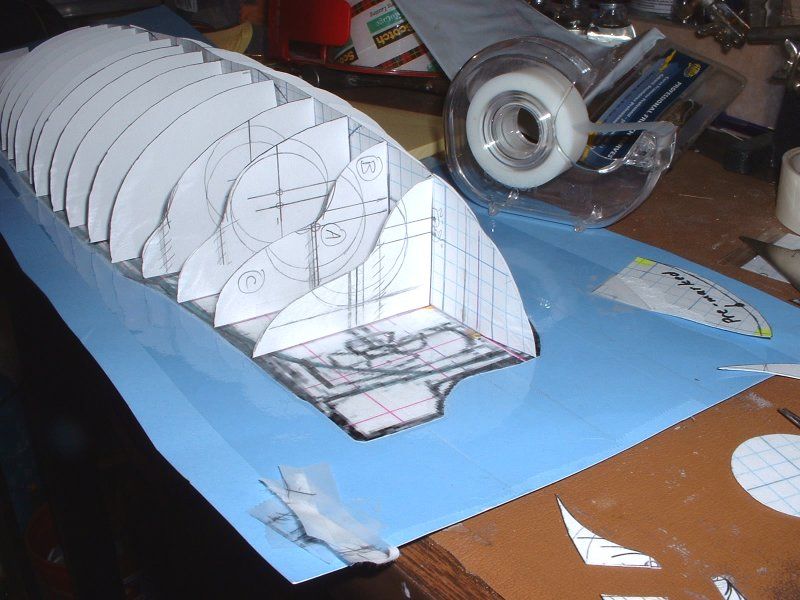

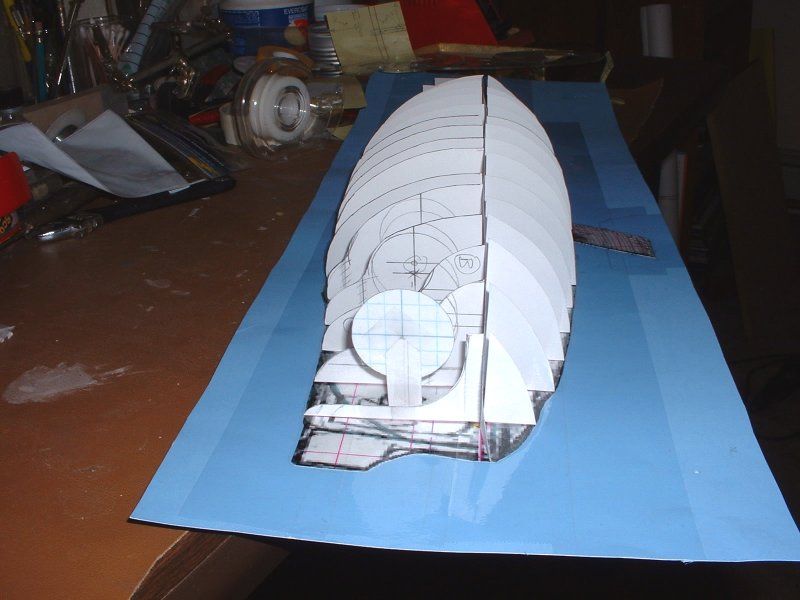

Okay. Things are starting to move right along, now. There's still oodles we'll need to adjust ... but we're getting a 3D shape roughed out. I had begun at the midsection, and moved backwards ... partly because the rear of the craft was probably easier to "see" than that strange bow! I had "saved that for later," on purpose ... figuring that making the stern "look like something" would give me confidence to deal with the bow.

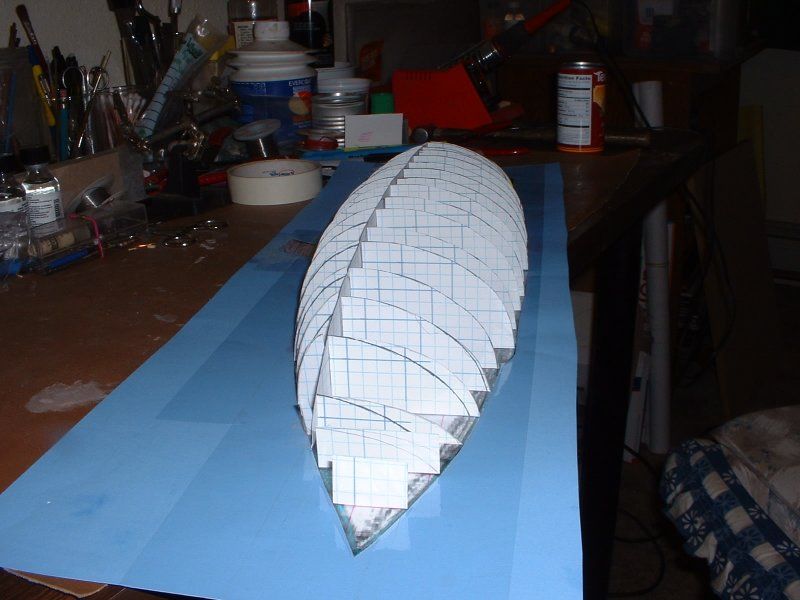

Sometimes, inertia is your biggest enemy. A good friend of mine has a saying I like, a lot: "Do something, even if it's wrong". I wouldn't advise such a course of action, if dealing with toxic chemicals or lethal voltage levels, etc. ... but when dealing with paper "slices": hey, why not?

Most of the info above, as you can easily see, can't possibly be ready for prime time! But it's a starting point. And perhaps more importantly: it's a starting point that's based, not on a "wing it, by eye" sort of "seat of the pants" vague feeling of what the original thing might have been shaped like. It's a good starting point, which sorta-kinda makes sense in some areas of the craft ... that began with a historical "blueprint"!

Had that blueprint included a plan view drawing (top or bottom) ... or even some nice, orthographic "end views" we could avoid a lot of what we're having to deal with, in these steps. But with this methodology, you can still get there. It takes serious thought, and some "bravery" (to not want to look foolish, or crazy; especially in these very early "baby steps" phases of "figuring out the shape") ... but the sytem works well enough to get you to the point where you can, without much fear of loss or embarrassment or whatever, start shaping "solid parts".

We're clearly not to that point, yet ... but compared to only having a side view drawing, and one cross section, we're light years ahead now!

Sometimes, inertia is your biggest enemy. A good friend of mine has a saying I like, a lot: "Do something, even if it's wrong". I wouldn't advise such a course of action, if dealing with toxic chemicals or lethal voltage levels, etc. ... but when dealing with paper "slices": hey, why not?

Most of the info above, as you can easily see, can't possibly be ready for prime time! But it's a starting point. And perhaps more importantly: it's a starting point that's based, not on a "wing it, by eye" sort of "seat of the pants" vague feeling of what the original thing might have been shaped like. It's a good starting point, which sorta-kinda makes sense in some areas of the craft ... that began with a historical "blueprint"!

Had that blueprint included a plan view drawing (top or bottom) ... or even some nice, orthographic "end views" we could avoid a lot of what we're having to deal with, in these steps. But with this methodology, you can still get there. It takes serious thought, and some "bravery" (to not want to look foolish, or crazy; especially in these very early "baby steps" phases of "figuring out the shape") ... but the sytem works well enough to get you to the point where you can, without much fear of loss or embarrassment or whatever, start shaping "solid parts".

We're clearly not to that point, yet ... but compared to only having a side view drawing, and one cross section, we're light years ahead now!

Comment