More links and stuff, to outside sources of info

Here's some more links, for anyone who wants to see recent conversations about the "real" Manassas.

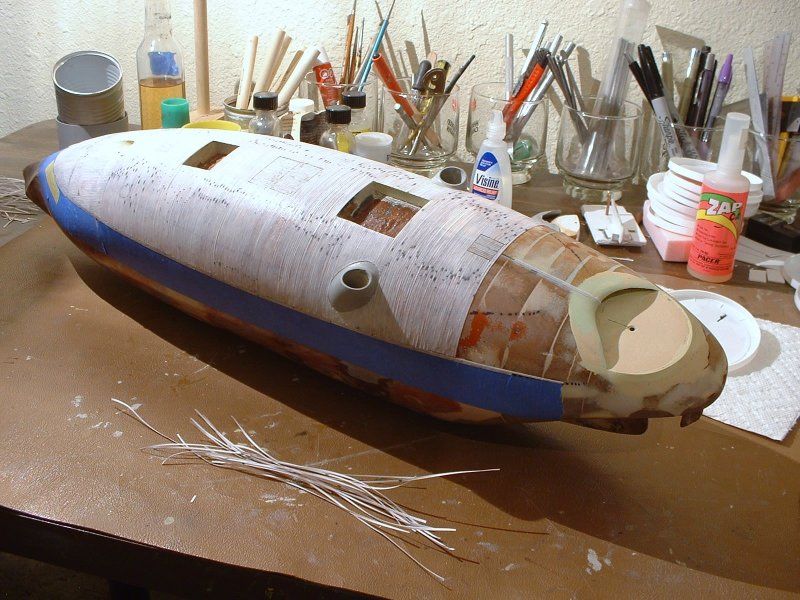

I ran across the web site, linked to above, sometime in the last week or so ... after ages of not having done anything at all, to follow up on the model I had built; or the published SF&FM article about that subject.

In short order, I was directed by the folks over there, to check out this other conversation, as well:

http://www.civilwartalk.com/threads/...anassas.81908/

As you'll see if you go there: that one, at present, has run to about seven full web forum "pages" worth of talk, back and forth, amongst students of the American Civil War, and/or fans of the CSS Manassas.

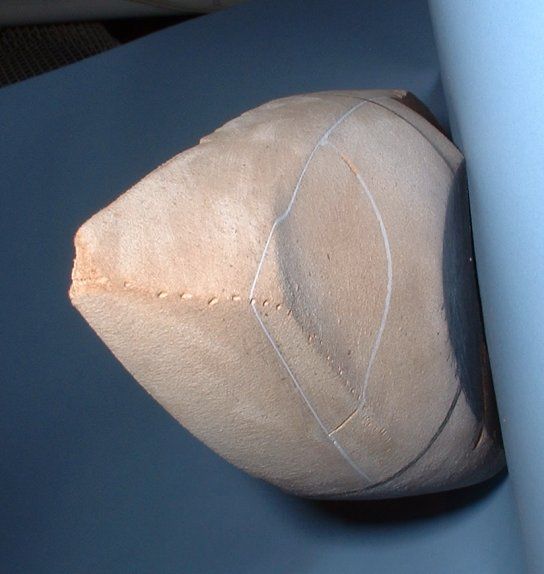

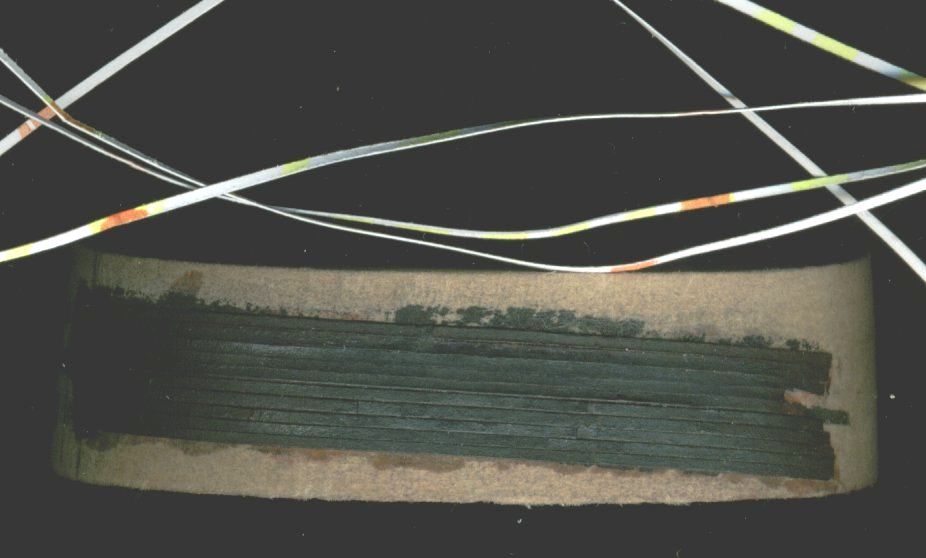

If any of the stuff that's in this thread interests you, those other two threads are also well worth reading. Amongst other things, they have a long quoted text, talking about the water ballast system on the boat that the Manassas was made out of. And the first photos I've ever seen, of the type of metal bars that were apparently used, on the real thing, as the exterior coat of iron armor.

While I realize this real-life machine / boat / vessel / whatever "gets little press" (considering how long it has been since it was first created, and did what it did) it does occasionally get some write-ups -- a few by hobbyists such as myself, here or there; and the occasional mention or write-up by historians, too.

There is one article in a semi-recent magazine, which talks about the first time the real life boat was in combat. See the March 2001 issue of "America's Civil War" magazine, for that. If you're looking for a copy of that issue, on some place like eBay (which is where I sourced my copy, some few years back) know it has "Custer at Waynesboro: Last Rebel Stand in the Shenandoah" as the cover's main article. There are three other articles mentioned on the cover; with the last one being, "Union Naval Blunder at Head of the Passes". The article starts on page 46, and runs through page 51 -- for a total of six pages. Not bad at all, I thought. Lots of interesting quotes from the people involved, back then -- and well worth the few bucks you'd likely give up to get a copy: assuming this subject matter fascinates you enough to read more about it ... and it sounds like (from this thread, and the ones mentioned above) that it just might.

There's at least one article written by a hobbyist, which I have a copy on order; but don't yet have in my hands. The seven-page message thread, linked to above, had a passing mention of an article in a model ship builder's magazine, back in 1985. If quick eBay searches pan out, I'll soon have that issue in hand, so I can see if there's anything in there that I hadn't already seen, elsewhere.

And, just to be fair, I really should give Gibbon's book a better review than the one I gave it, years ago. I don't remember what I paid for that book, but whatever it was, probably wasn't much ... and the book's best feature (from a scale modeler's point of view) is probably that it's got a lot of colorful illustrations in it. (And I do mean, a LOT!) Even if I question some of the research data in that book (and heck, even in my own writings about the CSS Manassas!), the pictures are worth seeing. And having around as "get into the shop, and go build something" motivation. Lots of crazy technology being tried out, in that arms race back then! And the pictures do "sell" the idea of how wildly off-the-wall many naval machines likely looked back then. Worth the price of admission, even if all you're gonna do is look at the pictures, once in awhile.

Also: there's a fan-published PDF "book" out there, by Steven Lund and William Hathaway. "Modeling Civil War Ironclad Ships" is the title. Link below, to that free download. Another very inspiring read, for those of us who like static models of naval vessels; and/or want to see them moving and animated and floating!

There's probably many more books and magazine articles out there, by fans. Chime in if you know of any!

Here's some more links, for anyone who wants to see recent conversations about the "real" Manassas.

I ran across the web site, linked to above, sometime in the last week or so ... after ages of not having done anything at all, to follow up on the model I had built; or the published SF&FM article about that subject.

In short order, I was directed by the folks over there, to check out this other conversation, as well:

http://www.civilwartalk.com/threads/...anassas.81908/

As you'll see if you go there: that one, at present, has run to about seven full web forum "pages" worth of talk, back and forth, amongst students of the American Civil War, and/or fans of the CSS Manassas.

If any of the stuff that's in this thread interests you, those other two threads are also well worth reading. Amongst other things, they have a long quoted text, talking about the water ballast system on the boat that the Manassas was made out of. And the first photos I've ever seen, of the type of metal bars that were apparently used, on the real thing, as the exterior coat of iron armor.

While I realize this real-life machine / boat / vessel / whatever "gets little press" (considering how long it has been since it was first created, and did what it did) it does occasionally get some write-ups -- a few by hobbyists such as myself, here or there; and the occasional mention or write-up by historians, too.

There is one article in a semi-recent magazine, which talks about the first time the real life boat was in combat. See the March 2001 issue of "America's Civil War" magazine, for that. If you're looking for a copy of that issue, on some place like eBay (which is where I sourced my copy, some few years back) know it has "Custer at Waynesboro: Last Rebel Stand in the Shenandoah" as the cover's main article. There are three other articles mentioned on the cover; with the last one being, "Union Naval Blunder at Head of the Passes". The article starts on page 46, and runs through page 51 -- for a total of six pages. Not bad at all, I thought. Lots of interesting quotes from the people involved, back then -- and well worth the few bucks you'd likely give up to get a copy: assuming this subject matter fascinates you enough to read more about it ... and it sounds like (from this thread, and the ones mentioned above) that it just might.

There's at least one article written by a hobbyist, which I have a copy on order; but don't yet have in my hands. The seven-page message thread, linked to above, had a passing mention of an article in a model ship builder's magazine, back in 1985. If quick eBay searches pan out, I'll soon have that issue in hand, so I can see if there's anything in there that I hadn't already seen, elsewhere.

And, just to be fair, I really should give Gibbon's book a better review than the one I gave it, years ago. I don't remember what I paid for that book, but whatever it was, probably wasn't much ... and the book's best feature (from a scale modeler's point of view) is probably that it's got a lot of colorful illustrations in it. (And I do mean, a LOT!) Even if I question some of the research data in that book (and heck, even in my own writings about the CSS Manassas!), the pictures are worth seeing. And having around as "get into the shop, and go build something" motivation. Lots of crazy technology being tried out, in that arms race back then! And the pictures do "sell" the idea of how wildly off-the-wall many naval machines likely looked back then. Worth the price of admission, even if all you're gonna do is look at the pictures, once in awhile.

Also: there's a fan-published PDF "book" out there, by Steven Lund and William Hathaway. "Modeling Civil War Ironclad Ships" is the title. Link below, to that free download. Another very inspiring read, for those of us who like static models of naval vessels; and/or want to see them moving and animated and floating!

There's probably many more books and magazine articles out there, by fans. Chime in if you know of any!

Comment