So, don't get your nuts in a bunch when you examine my work and assume I've 'overstated' the weathering. Trust me, American and even Japanese (true fanatics when it comes to post WW-2 ships husbandry) submarines get dirty.

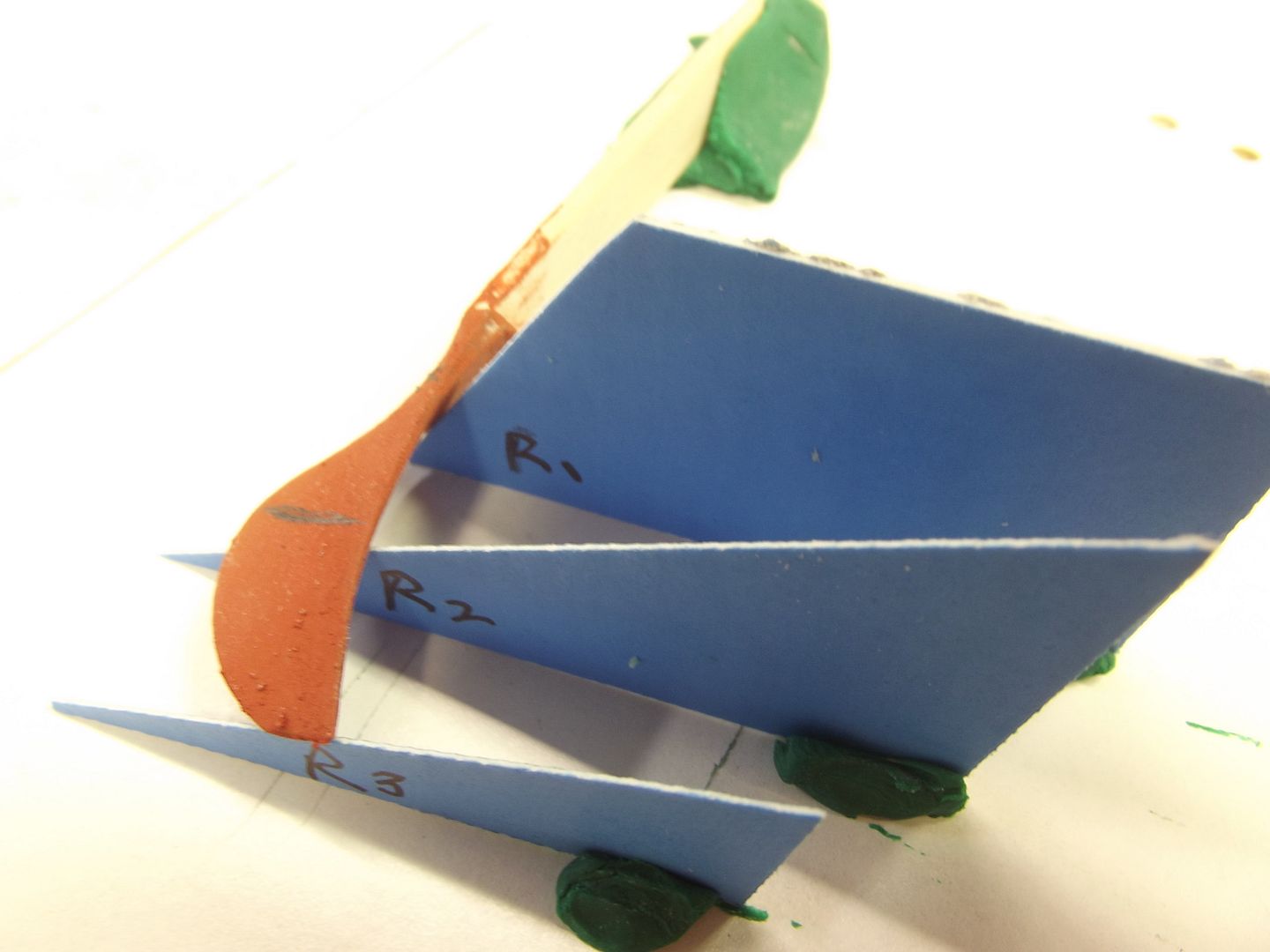

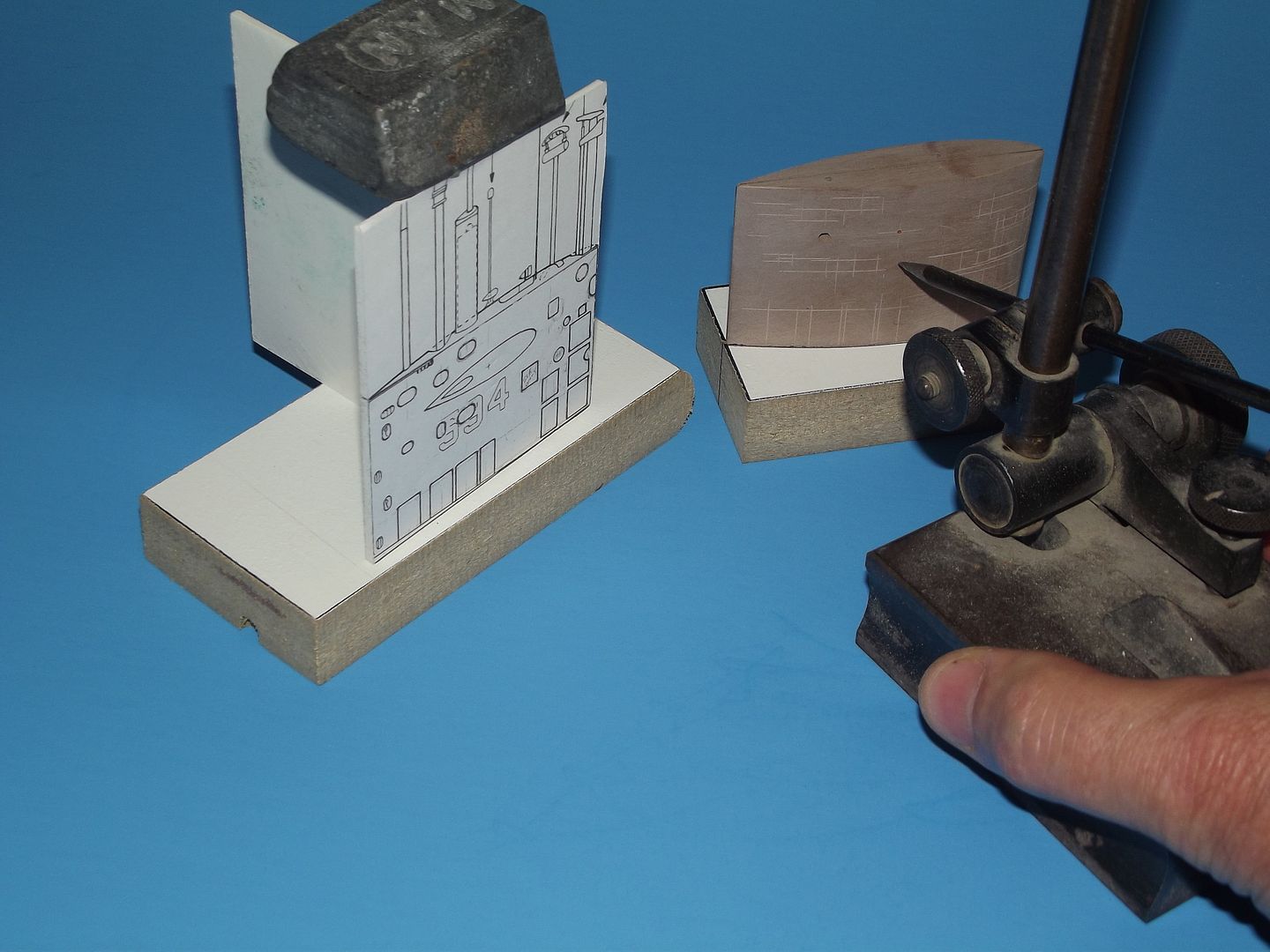

I first lay down a mask over the area where non-skid will be represented with a dark gray -- this to guide me on where to put the outboard elements of masking tape. Trust me, it's easier to get things symmetrical this way.

Comment